A dear friend came to visit for a two person writer’s retreat, and he asked me to help him get his book marketing game in order. I don’t want to call him out or anything (his name is Zack Dye, and you should read his poetry collection, 21st Century Coastal American Verses), but his online presence isn’t … present. And that’s a problem. As a publisher, I’ve found it’s a common one. So pull up a chair, lean forward, and listen to the advice I gave Zack. I think it’s advice a lot of authors can benefit from.

Ah, but I’m an author, too, so let’s start with a story. Back in 2013, when I released my first novel, I was still under the misapprehension that there was something shameful about self publishing. We were just coming out of the days of “vanity publishing” when the gatekeepers were still looking down their noses at this exploding part of the industry. I’d gone through hundreds of queries, had drinks with agents at writing conferences to pick their brains (they’re actually really wonderful, and the most ethical among them won’t let you buy the drinks), and I learned a lot, but at the time they were behaving like a dying breed, like dinosaurs looking up at the falling meteor and whispering, “Oh, shit.” Don’t worry. The best of them have evolved. But back then, the ones who were stuck in their ways thought self-publishing would ruin all of literature and also drive them out of house and home. Books have done just fine since then, thank you very much, and the agents who adjusted to an author-service model rather than a coveted gatekeeper model have done fine, too. But those deer-in-the-headlights agents still carried enough of that derision for self-publishing to scare me out of that route. There are still some people who look down on self publishing. There are also still people who think cars are bad and we should all have horses. It’s cute, but don’t let those people influence your business decisions too much.

I, unwisely, internalized their fear. Yet agent after agent told me my book was great but too niche to sell to the big publishing companies. (They were right.) So what was I to do? I decided to start a small press. At first, it was just a front, a facade on my house that appears to be brick. I then proceeded to make almost every imaginable marketing mistake. And I learned a lot. By the time I was ready to publish my second book, I’d learned so much I couldn’t stand the idea of my fellow authors having to start from scratch. But I didn’t want to write a whole book about how to publish a book. I write fiction and poetry, not self-help. So I found my people, fellow authors of sci-fi and fantasy, and made the company into something real. Now I have a co-publisher, we have 65 authors under contract, we’ve put out 36 wonderful books. 37 next month. Our authors include two New York Times bestsellers and the poets laureate of the cities of Tacoma, Washington and Oakland, California. And I still have to remind myself: We’re real! This is real! We built this real thing! I don’t think that will ever go away.

This shift from a guy with a logo and one product to sell to a co-publisher of a real company has changed my perspective on a lot of parts of the industry. [See: Agents. Not the villains who just say, “No,” all the time. Experts who do right by their clients and still serve an invaluable role in the industry.] My views on social media marketing have changed a lot, too. You’ve heard it before; you need to be on social media promoting your work even when it takes you away from your writing and feels gross. Well, that’s true, but the people telling you that don’t always explain why. You know why you love to write. You know why you hate social media. So unless you understand why you need to devote time to social media marketing, you’re going to default to the motivations you understand.

Maybe I can help.

Let’s skip why you write. It’s some combination of the four reasons Orwell laid out in his essay “Why I Write,” and your balance belongs to you. But let’s linger a bit on why you hate social media, because that will be helpful. My guess is that you have one of two reasons.

You don’t like wasting a lot of your precious writing time dealing with the often toxic, vile world of people at their worst, or

You really enjoy wasting your time and know it’s cutting into your productivity.

I get it. But here’s what we have to acknowledge.

The toxic, vile, world of people at their worst is exactly what every customer service employee you know deals with on the daily.

My girlfriend manages a restaurant. During Covid. (Guys, if you don’t know this, what women deal with online is a LOT worse than what we experience.) Well, my girlfriend has experienced that IRL! Do you think it’s potentially dangerous to tell a certain kind of man that you aren’t interested in his dick pics? (It is.) Well imagine telling that same kind of man that he can’t have his dinner unless he puts on the mask he’s taken an oath to the gods of chauvinism and white supremacy never to wear. But she keeps going back to that restaurant and telling everybody that they need to wear their masks because most people are nice about it and want to give her money for their food.

And you want the nice people to read your books.

Now, I acknowledge that the anonymity of the internet might make people write things they wouldn’t say to your face. And I will not be the person telling you to grow a thicker skin. That advice generally comes from people wearing crepe suits of privilege and is delivered to people who have to wear suits of armor just to leave the house each day. It’s not fair that you will witness and even experience horrible things online. It’s not right. It’s not easy. But if you want your books to be read, you have to care about the readers. I don’t judge people who keep private diaries. That’s a great mental health exercise. But they aren’t authors. If you write for others, you’ll have to deal with others. Engaging on social media is just as much a part of the job as talking to readers at book signings. (And there are some really unpleasant people who will engage with you in uncomfortable ways at signings, too. Because: People.) But don’t be deceived into thinking the toxicity in the world is limited to the internet, and if you can just avoid the internet, you’ll be fine. Have you seen the footage from January 6th, 2021? People can be just as awful offline. And people are your readers.

But maybe you’re like me. I’m in the other camp. I like social media way too much. It can be a dangerous time-suck. My work-in-progress is sitting in its file, seething, staring at me judgmentally, and the piles of books-to-read are starting to lean over me dangerously, and I will still find myself scrolling through twitter and Instagram and Facebook where someone will direct me to a video on Tik Tok and then there goes the evening. Sure, there are awful people online, but that’s not what gets in my way. My problem? There are way, way too many brilliant people online! Sure, there are the adorable pictures of my friends’ babies and pets (and sometimes babies and pets together!), but there are also the thinkers sharing ideas that inform my writing. These people allow me to justify the time. It’s not wasted. It’s research! And that’s not even a false justification. But ask anyone who writes historical fiction, and they’ll tell you that research itself can get in the way of your writing.

So, how do we push past the toxicity but limit the time to efficiently use social media to connect with readers? Here are some lessons I’ve learned the hard way so you don’t have to:

1. Your website is passive.

Back when I was making the switch from a guy with one book and a logo to co-publisher, I knew I needed a slick website, so I went to a friend who was a pro to get his help. He taught me one of the most important distinctions that’s served me well in all my investments of time online. “Your website is passive,” he told me. “No one will know what’s there until you direct them to it.” Before I understood this, I’d visited the websites of some of my favorite authors, people who are pulling in significant annual incomes from their writing, people who could afford to have really fancy, expensive-looking sites, and, with a few exceptions, I found that their sites were pretty blah, and some were downright cheap looking. Foolish me, I thought, “Ha! I will have this competitive advantage by having a fancy, expensive site! I’m so much smarter than these incredibly successful authors!” Nope. Turns out they’re successful because they’re a lot smarter. They knew (or hired smart people who knew) that the website doesn’t make much of a difference. You should have one. It can be a free one. It’s basically a business card with links to your books, your bio, and a place to announce events. And even then, no one will know about the events you identify there unless you tell them elsewhere, because your website is passive. There are authors who develop a following with blogs, but the website is just a repository for that content. The audience is drawn to it because those authors go to social media to let folx know when they’ve added a post. Unless you are so successful people will search for your name, don't sweat the website. And if you are so successful people are searching for your name, don't sweat the website.

2. Your follower count matters.

When I was researching querying agents, one of the pieces of advice I kept coming across was to mention my follower count. I hated this! It felt like this impossible impediment to new writers. But as a publisher, I've totally flipped on it. Here's a secret those pieces on querying didn't explain. Shhh. Maybe they don't want you to know this. I'm going to tell you anyway. There are, secretly, two different things that one piece of information tells the prospective agent. The first is obvious: If you have a million followers on Instagram or twitter, you have an instant potential market for your book. Great for them. It still doesn't make it a done deal. Maybe those million people are really into the cute pictures of your dog and would never buy your 500 page historical novel about the Visigoths. (But some would!) But what if you only have 50 followers on twitter and 53 on Facebook and most of those are the same 48 people? That tells the agent not to publish your book, right? Wrong! It tells the agent you are on twitter and Facebook. I have published people who aren't. Even if I want to, I can't tag them in posts about their book. I can't increase their fanbase because they are digital ghosts. I can't say to the public, "Go build a relationship with this author so you will hear about their second book and buy it right away." If I publish their book, I am assured I will have to do all the marketing myself, and their fanbase won't grow much over time. If you want readers, you must behave as though you are interested enough to meet them where they are.

3. The platform doesn't matter much.

Should you be on twitter or Facebook or Instagram? As a publisher, I really don't care. If you have mastered making Tik Tok videos and have a million followers there, great! If you are the queen of Snap, great! Got a YouTube channel with a million subscribers? Awesome. Whenever a new platform comes out, there's the inevitable buzz about how people have developed huge followings on “book twitter” or “bookstagram” or “book Tik Tok.” Here’s the reality: If there are lots of people there, and if you can connect with those people, that’s the key, not the platform itself. Now, the platform will have a structure, and people who navigate that structure best will connect with the most people there. Are you really great on video? Maybe you make wonderful, short videos of yourself and develop a following on Tik Tok. Maybe your videos are ten minutes long? YouTube. Are you a talented photographer? Instagram is for you. Are you witty and able to write snappy comments that will be shared a lot? Go to twitter. Do you like to engage in longer conversations? Facebook or Reddit. There are millions of potential readers on any of these platforms. You just need to figure out how to connect with them.

4. What you post DOES matter.

You may have heard of Talia Lavin. She’s @chick-in-kiev on twitter. She loves to post about swords. She’s also an expert on anti-Semitic and white supremacist hate groups. She’s even infiltrated some of them and has written a great book about anti-Semites and white supremacist hate groups in America, Culture Warlords. She tweets a lot about hate groups. She tweets a lot about swords. She rarely reminds people to buy her book. But she has it clearly identified in her bio, so when I kept reading her tweets, thinking, “Who is the fun person with an obsession with swords? Wow, she sure makes insightful comments about hate groups. Oh, look, she wrote a book about that,” then I found myself buying her book.

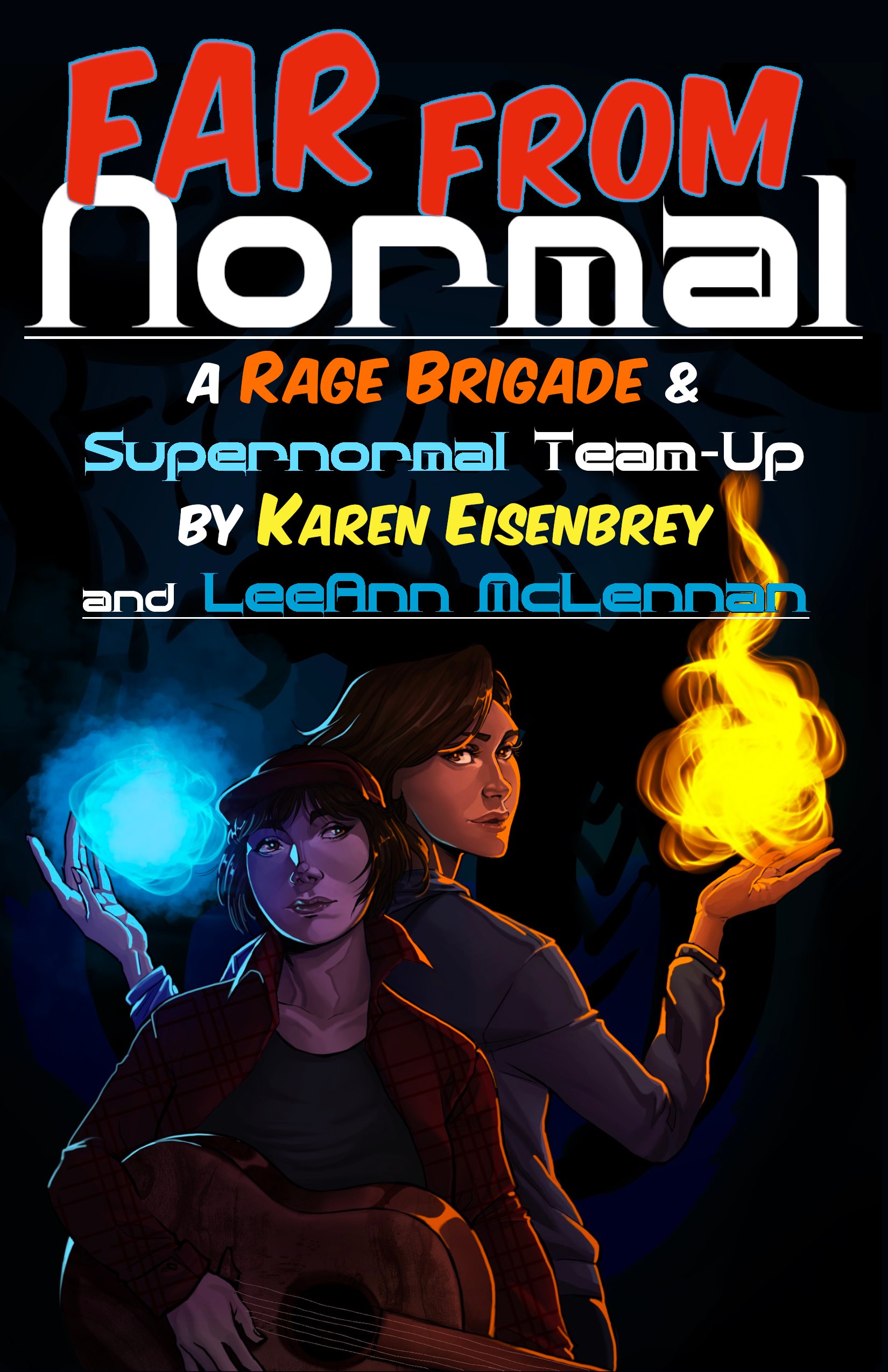

Or, take Karen Eisenbrey. She writes about band names she finds. She mentions them on twitter and Facebook, and then she posts a regular blog about them. Her posts are funny. Oh, and look, she wrote a couple YA novels about a young woman who starts an all-girl garage band in Seattle (and also acquires super-powers), The Gospel According to St. Rage and Barbara and the Rage Brigade. The interest in band names doesn’t feel forced or contrived; it’s really her thing. She’s a musician herself, and has been the drummer in some Seattle garage bands (as well as playing bells in her church’s bell choir). Her posts drive me to buy her books because I’m interested in her, and now I like her work and will come back for anything she writes.

Or consider Kate Ristau. She decided to challenge herself to learn to draw by drawing a dragon every day for a year. The first dragons were laughably bad. The last ones were really cool. It was fun to follow her on twitter and Facebook and Instagram, see the progression, and be reminded to break my own fixed-mindset thinking about what I’m not good at. Meanwhile, she was also writing about parenting (including essays that were picked up by the Washington Post and New York Times), and about her writing. She rarely says, “Buy my middle-grade Clockbreakers series or my YA Shadow Girls series.” But when I saw that she’s got a graphic novel, Wylde Wings, coming out, I rushed to pre-order it because her social media has helped me form a relationship with her and her work. Did Talia Lavin’s posts about swords detract from my interest in her journalism about hate groups? Did Karen’s fascination with obscure band names keep me from reading (and loving) her Wizard Girl fantasy series? Did dragons, who don’t even appear in Kate’s Shadow Girl series, drive me away? These things helped me get to know these writers so that I was more interested in their work.

Personally, I post a lot about my support of #BlackLivesMatter and feminism, and I also post pictures of the flowers in my garden and of my dog. I’ve received some push-back, sure. I get hate mail and sometimes even death threats. It’s unpleasant and sometimes quite scary. But I console myself with the knowledge that every single one of the people sending me these threats is taking a little break from abusing women and people of color online, and I know they are a LOT worse to the people they hate the most than they are to the middle-aged cishet white guy who is voicing support for women and people of color. Also, since they rarely come right out and say why they are so angry at me, for all I know, maybe they just hate flowers and dogs. Meanwhile, the people who like that a cishet white guy is sharing about #BlackLivesMatter and also likes flowers and dogs … those folx will like my books!

5. You can’t please everyone online. Don’t try.

I’ve come across a debate a handful of times online about whether or not writers should engage in political discussions while trying to promote their work. I understand where the fear comes from. Those of us who don’t have very many readers look out at the landscape of a highly polarized world and say, “If I have twenty readers, and writing X will alienate half of them, I’d better not write X.” But that formula is wrong. We are so polarized that almost everything has taken on a political valence. (Read Ezra Klein’s Why We’re Polarized for some insight into the origins of this, but also into the way the mega-identities have consumed so much of what was previously considered apolitical before.) You cannot escape it. I understand where the impulse to avoid politics comes from. Some people want to avoid confrontation. Others don’t feel knowledgeable enough to be equipped for such conversations. But here are two facts you must internalize:

First, if you can avoid uncomfortable confrontation when you don’t have sufficient knowledge to engage in it, that necessarily means your existence is not threatened. People who are threatened already live with that discomfort and know they can’t wait until they acquire knowledge in order to defend themselves. This goes for the people I see as genuinely threatened (women, people of color, the LGBTQIA+, religious minorities, immigrants), but I have to acknowledge that it also goes for the people I see as the oppressors who feel they are under an existential threat if others gain equality (men, white people, Christians, the cishet). These people, whether their fears are legitimate or not, cannot bow out of political dialogue because they genuinely believe they may be, at best, disempowered, and, at worst, eradicated if the other side has their way. If you feel you can afford to check out, you don’t think your existence is threatened. Checking out is an expression of privilege.

Second, if you’re a writer in the modern world, you’ve taken a side anyway. Are all your characters male, white, Christian, cishet, and native born? If so, you’ve certainly taken a side. If not, and if you’ve written a character who has agency and any identity not on the approved default identities list, you’ve also taken a side. Attempting to present yourself online as someone who is non-partisan amounts to a bait-and-switch; your reader will find that you care about women, people of color, gay people, trans people, people with disabilities, religious minorities, and will either feel betrayed because you didn’t stand up in your online persona, or they will feel betrayed because they want that group disempowered and you kept your affinity for people with those identities secret. You certainly don’t have to post about politics all the time like I do, but don’t shy away from defending (or persecuting, I guess) the kind of people you lift up (or push down) in your writing.

6. Count the eyeballs. Divide by two.

That impulse to avoid offending is predicated on the formula that the number of readers is fixed, and the offense will limit it. This misconception is the number one thing you need to break when considering social media. And this is really hard for us, as humans. Our ancestors lived in groups of about sixty, and our brains evolved to handle inputs from a social group in that context. If even one or two people, out of sixty, felt your ancient ancestor was a severe enough problem for the group, it really was an existential threat. Because humans can’t survive alone, if your ancestor got kicked out of the group, she died. And if she died, she’s not your ancestor. You are the product of millions of years of humans who knew how to get along, and who changed their behavior as soon as someone said, “Hey, that’s not cool.” So when you wade into social media, and when a hundred people click on a heart or a “Like” button, your brain doesn’t know what to do with that. It’s an instant abstraction. “People like me.” You release a little hit of dopamine, suck on that for a second, and move on. Because “people” isn’t Aunt Judy or Mom or Maria or Latania. But if even one person says, “You suck!” or even something far more tame like, “I disagree,” or “Well, to play devil’s advocate,” you chug a cocktail of cortisol and adrenaline so you can fight for your life because, remember, your ancient ancestor’s life really was on the line. One or two critics will veto the expressions of hundreds, thousands, even millions of other people. In the modern world, you’ll feel upset and anxious for the rest of the day, like those moments when you have to slam on the brakes to nearly avoid a car crash and you’re shaken even when you get home safely.

So, some primitive part of your brain says, if you can just keep the number of interactions very small, you can protect yourself from Bob and Vlad who may be pseudonymous trolls with nothing to do but harass people all day online, but who feel like very distinct individuals in the moment. But you also want your work to be read by hundreds, thousands, even millions of readers. Maybe, the primitive part of your brain calculates, if you just produce really high quality work, it will be discovered and promoted by other people, and you’ll wake up one day to find that you’re wildly successful. And look! You didn’t even have to waste time online, and that gave you more time to work on crafting all that excellent writing!

Not only is this dream unrealistic, it’s selfish and dangerous to your own writing. It’s selfish because, when you hope other people will promote your work, you are counting on them to endure that unpleasantness on your behalf. The random fan of your work, Cindy from Tuscaloosa, who says, “You should buy her book. I liked it,” is subject to Bob and Vlad saying, “No it isn’t. You’re stupid for thinking so,” (and, let’s face it, a whole lot worse), and that will produce exactly the same threatened feeling in Cindy’s brain that it will produce in yours. Should Cindy not take an attack on her tastes as personally as you would take an attack on your work? That’s debatable but irrelevant in the moment Cindy’s brain and your brain are deciding to mix that cortisol and adrenaline cocktail. Of course, being online will not protect Cindy from Bob or Vlad, but depending on Cindy to do something you wouldn’t do yourself is unfair.

Second, avoiding the spaces where your readers converse so you can write in peace will not make you a better writer. I’m sure I’m not the first to point this out to you, but writers develop an ear for eavesdropping in public spaces to improve the way we capture voices in our dialogue. We are trying to accurately reflect the way people speak. If you stayed out of all public spaces in an effort to preserve your writing time, the quality of the dialogue in your writing would suffer. The same goes for the written word. You can hide away from social media and read really good writers who can show you how people interact online, but that’s mediated through those writers in a way that’s akin to trying to describe romantic relationships based on what you’ve seen in rom-com movies. Some of it’s right, and some of it’s wrong, and you won’t know which is which. If you want to write the way your readers write and read online, you need to be there. And this isn’t just for that scene in your book that takes place on twitter or in the comments of an Instagram post. Your readers, through their interactions online, are telling you what they care about reading.

This is most easily illustrated for old fogies like me who remember the pre-Internet era. Imagine if, in 1988, you received a Christmas card in the mail from a friend who included a picture of their cat. Not that big a deal, right? But then, every month after that, they’d sent another picture of their cat with a note asking you to send a picture of your cat. And then, one time, when Susan was over at your house, she’d seen the letter sitting out, and she’d said, “Oh, you’re on Gary’s mailing list, too?” And then she’d revealed that Gary sent those out to a hundred people every month. “He must spend $22 a month on postage alone!” Susan would have said. (Stamps were only .22 in 1988, but $22 then is $50 now.) And you’d agree that Gary’s interest in seeing pictures of other people’s cats was very, very strange. Now, younger folx, imagine I said to you, “I have this friend, Gary, and he probably clicks ‘like’ on a hundred pictures of cute cats each month on Instagram. Isn’t he weird?” You’d say, “No, he’s not, Boomer. You’re weird for thinking that’s weird.” Readers have told us they like cute cats … and dressing up as comic book superheroes, and watching people open packages, and watching people play video games, and comparing everything to Nazis except actual Neo-Nazis. If you aren’t engaged online, you’re writing for Susan in 1988 rather than Gary, only Susan in 2021 is also Gary but she wears a cat costume on her OnlyFans and whispers meow to ASMR fans and licks herself clean for people who pay extra … and you want her to buy your book!

So, here’s the new formula: Count the eyeballs and divide by two. If you can get a thousand eyeballs to look at your cat pictures on Instagram every day, later you can ask 500 people to read your book. If you can get 10,000 people to retweet your joke about Matt Gaetz’ enormous forehead, you can comment on that tweet later to those 10,000 people to read your book. If you can start a really rich and thoughtful discussion on Facebook that involves 100,000 people … okay, ten people … okay, nevermind. There aren’t rich, thoughtful discussions on Facebook. Count the eyeballs and divide by two. How many people are seeing your posts on Facebook? 40? And ten are friends who already bought your book, and ten are people who will say, “Congratulations!” when your book comes out but never buy it in a million years? And the other twenty will unfriend you if you ask them to buy your book but might buy it if someone else recommends it? Then why are you spending so much time on Facebook? Count the eyeballs and divide by two.

7. Make Social Media Better

If you’re still feeling reluctant to dive into social media, here’s a tip that will improve your experience and everyone else’s: Make it better. The philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his attempt to design ethical rules around “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” but without the religious baggage and in a more consistent, systematic way, came up with this idea that moral rules (or maxims) should be universalizable. In other words, we should think about what the world would be like if everyone else made the decision we were about to make, and if we would want to live in a world where everyone made that same choice, it’s the right choice. There are some flaws with this idea, but it would all serve us well online. Imagine if everyone’s feed were a constant litany of requests to buy their product. Gross, right? So don’t do that. But if everyone were making art and not telling you about it, that would be annoying, too, right? So you should occasionally remind people that you have created art they might enjoy. In between those occasional posts, what can you do to make social media better? Well, don’t you like it when people tell you they like your work? Go find someone who has created a TV show or a book or a painting or recording of a song or a video of themselves doing a dance routine, and, in a way that doesn’t creep them out, tell them they are great. Do you like it when someone tells other people to read your work? Then tell other people to read your favorite writers’ work. Do you like living in a world where the voices of the dominant culture drown out other voices? Me neither. So, on twitter, I make sure I am retweeting more women and people of color and the LGBTQIA+ than I am posting tweets by cishet white men (including myself). (“But Ben,” someone says, “is that universalizable? What if everyone paid more attention to voices that are commonly silenced? Wouldn’t we get to the point where cishet white men aren’t getting any attention? You wouldn’t want that, would you?” To which I say, “Let’s give it a try.”) Do you feel uncomfortable when you see someone post a “joke” which amuses some people but hurts others, especially if the post amuses people who have more power while harming people with less power? Yeah, that’s not a joke. It’s bullying. Don’t do that. And if you see someone behaving badly online, imagine how you wish everyone would react. Wouldn’t it be great if everyone, especially the kind of person that individual is likely to take more seriously, would tell them to knock it off? Then do that. Would the internet be better if that person were reported for harassment? Then do that. You can’t make social media a kind and humane space all by yourself (and if you could, that wouldn’t be kind or humane), but you can make it better through your own engagement in a way you can’t by avoiding it. So, if you recognize that social media is a necessary means to connect with readers but also that it’s sometimes scary and gross, get on there and make it a tiny bit better through your own positive behavior.

8. Find a healthy balance.

You need to get your writing done. You need to be on social media to let people know you have something worth reading, or all that time spent crafting the work was wasted. So you have to find a healthy balance that allows you to do both successfully.

I don’t know how to do that yet, so I don’t have any useful advice in this department.

Sorry.

Oh, but here’s something that might help: Don’t try to create all your own content. It’s too exhausting, both for you and your reader. Instead, promote other writers by boosting their content. If it’s uncomfortable to promote your own work, you may find it more comfortable to promote others’ work. I do! So hop online, create an account or two on some different platforms, and tell me about something you’d like to see more of, and I’ll follow you, share that out, and tell folx to like your stuff, too. And if you found this helpful, share it out so your fellow writers let me know about their stuff, too. Helping one another is a virtuous cycle. Let’s jump on it and take a spin!

Lastly, if you are a wildly successful YA novelist who hates trans people, remember that there are rare instances where your online behavior can completely undermine people’s enjoyment of your work, so maybe you can just stay off social media entirely if you’re incapable of using your considerable power to help people rather than hurting them.

---

Benjamin Gorman is mostly on twitter at @teachergorman, often on Instagram at @teachergorman, reluctantly on Facebook here, and even tried Tik Tok a couple times here.